Derf Backderf began his career as a political cartoonist, and he was first published in the Ohio State Lantern. “I was all of 20 years old…and here I was marching in to that newsroom and [dramatically dropping papers on a desk and said] ‘here’s my comic why don’t you print that?’ I don’t know where that chutzpah came from, I have absolutely no idea…I just kept cranking out those comics and I just never had that fear of being accepted or pissing people off or making a fool of myself. And I did all those things many times, and yet I never thought about it.” One time, he was so brash that he had to “flee” OSU for a few days “because of outrage over a cartoon that ran in the school paper bashing a football player who ran afoul of the law.”

This “comics creator” went on to become a staff political cartoonist for several years, and lamented that being a traditional staff political cartoonist “is pretty much dead at this point [because of] the newspaper apocalypse.” He also spent 24 years writing cartoon strip The City. In some ways he regrets having written the strip for that long, “and that’s okay; everything has its time and certain things fit better in certain eras than in others, and you have to know when to drop the mic and walk away.”

Around 2000, he started moving to “longer form comics,” in part because he saw the “newspaper apocalypse” coming. He “can’t imagine trying to write in such a small space again. Why write in five panels when I have 300 pages to do it now?” He also feels he is much better at the “long form narrative” – aka graphic novels – than he was at comic strips. He commented that while he had a lot of fun writing The City, “I basically spent a quarter of a century in the wrong genre.” Yet, he stated that “a graphic novel is a big comic book.” Curiously, in other countries, especially France and Belgium, “comics are held on the same level as film and the written word, and photography and poetry; it’s absolutely even. It’s only in this country that we’re kind of this backwards attitude about comics… [Yet] particularly millennials are reading comic books from a very young age in staggering numbers. So they’re growing up with comics and have a much greater appreciation for comics than a lot of older generations.”

He illustrated the personal nature of graphic novels. First, he explained about “floppies.” A floppy is what one might consider a standard comic book (think Archie or Marvel or DC) that is about 24 pages, and they “flop” when you hold them up. They are generally part of a continuing series and “go on forever.” Floppies are usually a corporate product, produced at a corporate level with marketing campaigns, strategy sessions and so on. They are commonly produced by a team and tend to have “content constraints.” In contrast, graphic novels “are much more personal in terms of art… A graphic novel tends to be the work of one person, one creator. In the case of my books, every word, every line, every shade is put there by me, by hand and so what you’re getting is a very personal piece of work.” He added that “graphic novels are a lot more wide open, there really are no constraints. There are all kinds of genres of graphic novels and they can be challenging, they can be revolutionary, they can be controversial.”

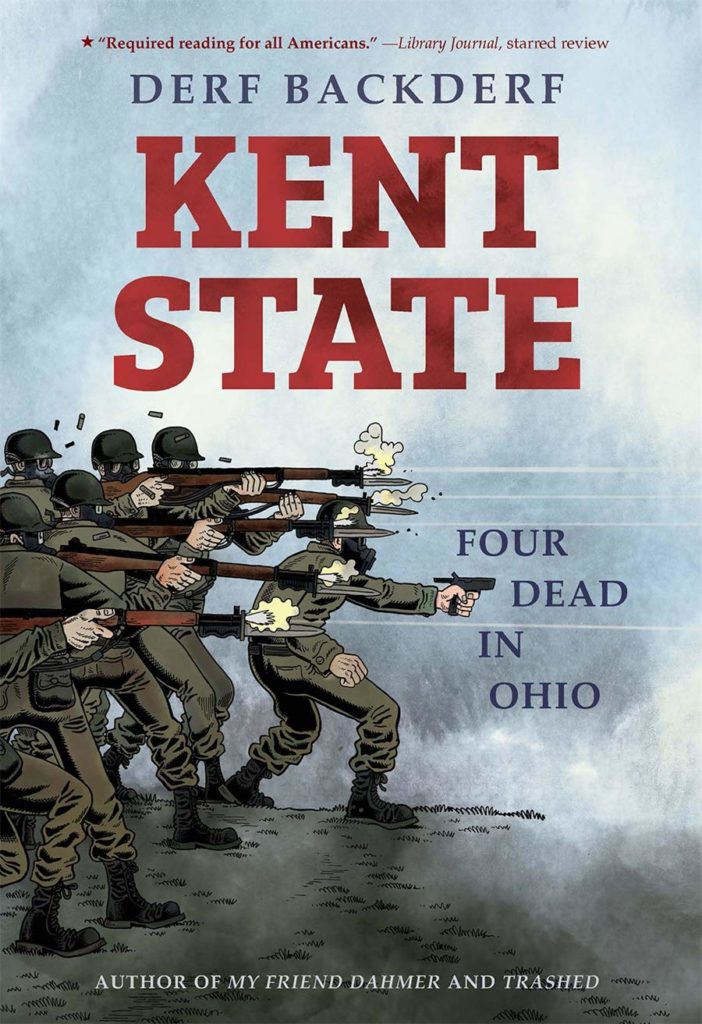

Indeed, three of his books – Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio (2020), Trashed (2015), and My Friend Dahmer [yes, that Dahmer] (2012), are challenging if not straight up controversial. In fact, Dahmer was banned just last year in Texas. Yet, Kent State was extremely personal to Mr. Backderf, and originated as a book based on his own personal experiences. He has “always been interested” the events at Kent Sate in May 1970 since he was a kid, and the opening of the book explains his connection in detail. “It really affected me. If you were there – literally the entire state of Ohio froze in its tracks on May 4. Many people were horrified, most people were stunned, some people were furious – it ran the gamut. But everybody just stopped and it really was a defining moment out of that era – it was a bloody climax of that era.” Even though young, he was aware of what was happening around him, and it “actually kind of sparked something in me – intellectual curiosity perhaps. I started exploring the world around me because up to that point, I was 10 years old…I was just a kid, living out a clueless life. From that moment on I really started to look around a little better. I can trace a straight line from Kent State to my intellectual growth…” to his degree in journalism, then being a political cartoonist and on. “It goes right back to Kent State. Everyone has that moment and something sparks it; this was mine.” To see a “bump in the road” of his life, read Trashed (in development as a screen play).

For Kent State, he “purposely narrowed the focus…I did not want to make it this big sweeping story and that’s why I focus on those five people. The story is told by the four who were shot and the one guardsman. The story is told entirely through their eyes. What I’m doing there is putting the reader right on the ground next to them, and we walk through the story right next to them; we see what they see and experience what they experience.” For this author, “that’s how you make this story personal, and if you make it personal, that’s where you find the emotional power in the story.” The story takes place over just four days; “the story ends when they are cut down.”

Mr. Backderf’s writing process is “a lot of work, it’s slow going but it’s a fairly simple process, or at least is is for me.” He begins with “thumbnails – words and pictures together usually always. I may make notes about what I want a scene or a chapter to look like, or story art.” He then begins to sketch the individual panels, “and this is where I work out most of the details.” He had his concept for Kent State from the beginning, and “the challenge was in doing all the research, digging through the archives, doing the journalism, figuring out what happened where, when, why… It’s a bit like detective work.” This part took approximately two years, and the drawing itself took approximately two years although some research continued as well. The “nuts and bolts drawing” was the most difficult part of the book and there were many things he had not tried before including big crowd scenes, military scenes and equipment, and “lots of characters and people, and sweeping vistas.” The key is to make each scene “visually appealing and make the reader want to continue reading.” Notably, this book is a dramatic recreation, and Mr. Backderf has never tried to pass it off as entirely nonfiction although every panel has at least one source, with most having three or four. However, the book is largely drawn from the accounting of Chris Butler, a mutual friend of Jeff Miller and Mr. Backderf. His goal was to capture the emotion of that account. “I think I pulled it off!”

Unfortunately, Kent State suffered greatly in sales, publicity, marketing and appearance due to Covid; “it was a nightmare.” He missed tours in the US and Europe. He missed meeting fans, live talks and appearances. He felt that so many opportunities “were snatched away” by Covid. It was difficult to write for a while, and he lost a very close family member to Covid, as well as a friend. Only recently has he been able to get back into writing, and he finds “uplifted” by work.

Yet, he is doing what he has wanted to do since he was a small child. In fact, he still has political cartoons he drew at the age of 10 about the events at Kent State. In high school, he was in the marching band (tuba), and found it “very helpful in terms of skill building – concentrating on a different art form.” The work of breaking down a piece of music or working on difficult fingering were skills he applied to his art. He also did theater and school newspaper, as well as “all my subversive activities on campus.” This including “running fake candidates for student council and all kinds of stuff that got us into various degrees of hot water.” He wishes he had known as a teen that “it gets better. Adolescence is something that you survive.” As for advice to aspiring cartoonists, Mr. Backderf advises “just make comics. Making comics is really easy – you sit down with a piece of paper or tablet and you are making a comic. Now, making good comics – that’s hard. But to make good comics you have to start by making comics, and you just do it.”